Me, Myself and Misconceptions

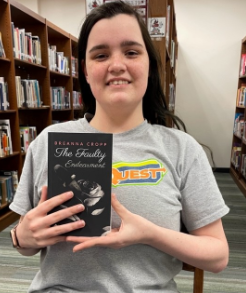

My experiences, learning moments since being diagnosed with epilepsy

After freshman orientation with my sister this summer, some friends and I made our way to the crazy busy counselor’s office to check our schedules before school started the next week. The lady in the front desk politely asked for my school ID number and started pulling up my schedule. But, of course, then came the giant, flashing, red warning box across the screen, and everyone around the screen turned to stare at me.

I am epileptic. Epilepsy is a neurological disorder known by the sudden episodes of sensory disturbance or loss of consciousness – or seizures – that come as a result of the abnormal electrical activity in the brain. Yes, now is when the questions and condolences start flooding in. Teachers asking for “plans of action” if I have a seizure in class, students giving me awkward sympathetic glances and friends and family pouring out their worries and trying to protect me somehow. It’s uncomfortable, and my stomach feels tight as I try to smile and make them understand that I don’t need – and I definitely don’t WANT – to be babied and worried over. I worry that a majority of the time it scares everyone else more than it even scares me.

That’s not to say that seizures aren’t scary. Having no memory of how much time had passed, and then coming to and not recognizing anyone or knowing where you are is far from a tranquil experience. However, people generally do not take the time to consider my personal factors and it is usually assumed that being seizure-prone means I’m just like anyone else who has seizures, and that is far from true.

My first seizure was during the summer of my sophomore year. My family and I were camping near Red River, New Mexico, and I had been catching a cold right before we left on vacation. It was July 3, so most of my family decided to go into town for the Fourth of July parade that evening. But, because I was so wiped out from walking around and hiking all day, I decided to stay back at the campsite with my older sister and go to sleep at a decent time. But, instead of sleeping like we planned, my sister and I ended up staying awake and talking and joking in the tent together until long after dark. Right around the time my parents planned to be home, our conversation had progressively become less and less intelligent as we got more and more drowsy and seemed to enter into a sleep-deprived delirium. I could feel my jaw and various other muscles randomly clenching and then eventually loosening again, but I thought nothing of it, believing it was merely the cold making me shiver. But then it happened.

My whole body felt slumped and I suddenly blanked out. A few minutes later I could see again, and there were people all around me. Their faces were filled with concern, and I could tell they cared; but I couldn’t remember who anyone was, and I didn’t know what they were so worried about. Suddenly, all I could feel was the pure fear of the unknown. Slowly, I remembered my mother, and eventually the rest of my family were recalled to my memory. The health care professionals who happened to be camping in the next site over told us it was probably a one-time thing, and not to worry as long as I was fine now.

For the next few months I was seizure-free and totally back to normal. I remained that way until the first tech week for the Raider Theatre show “Chicago” came around in December. I then had my second seizure after coming home sick one day, and my mom quickly drove me to the hospital where I missed three days of school and got all sorts of scans done before finally receiving the news that I was, indeed, epileptic.

When someone hears the term “epilepsy,” the first thing they assume is that I can’t go to parties or movies with any flashing lights. However, for my particular case, I can sit in a room of flashing strobe lights and have no reaction. My seizures are only caused by two everyday factors: sleep deprivation and stress. This explained why I had my first seizure when I was already sick and away from home, staying up late, and my second seizure when I became overly stressed out from theatre technical rehearsals for a big show. So, as a high school student in AP classes and lots of extracurricular activities, my epilepsy creates a problem with staying up late for school assignments and having extra social events outside of school.

But, even with all the limitations set on me by my epilepsy, I can’t say it’s all been bad. I believe hardships don’t become disabilities unless you allow them to. Since I was diagnosed as epileptic, I have become much more aware of my physical limitations and take much better care of myself. This forced me to start prioritizing and realize which things I needed to cut out. I actually became more confident in myself, and I appreciate my friends and family much more. I decided on goals for my future and really started working toward making those things happen. I started noticing my own strengths and trying to help others do the same as I realized these “disabilities,” or circumstances and tribulations, don’t make us who we are unless we allow them to. We get to choose our perspective and, though we can’t always change the facts (I can’t simply go back and delete the fact that I have seizures sometimes), we can choose to let it help us. These trials are what let us show our strengths to ourselves and others, and we can then use the wisdom we gained to empathize with others when their hardships come.

I have now been seizure-free for just about two years. I have one more EEG scan in December to decide whether or not I can start coming off of my medicine next March, or if this will be something I’ll deal with for the rest of my life. I’m hopeful for the best, but I know that whether or not it changes now, I wouldn’t go back and get rid of my epilepsy even if I could. It’s a part of my story now, and after all, who ever heard of a great character with no adversity.